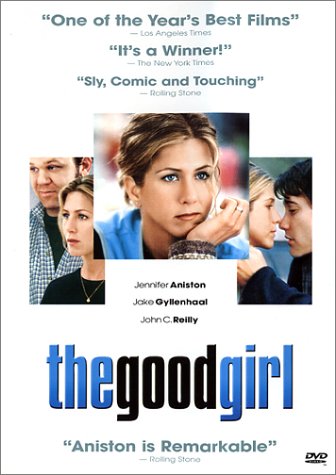

Although many women authors took this advice, there is still this “Angel-Monster” dichotomy throughout various artistic forms today. In numerous male-directed films, the female characters are often labeled as either “good” or “evil”; not usually seen as character deserving of multiple motives. Take for example the movie “The Good Girl”. The director tried to depict Jennifer Aniston's character as entirely confused and lost, perhaps providing some explanations for her ways of betrayal. However, males that watch this film often seen Aniston's character as “selfish and evil”, the ultimate antithesis of ideal female behavior.

Gilbert and Gubar explain that women are supposed to angelic and pleasing to men (Gubar 816). In 1865 John Ruskin commented about the role of women in a patriarchal society. He stated, “Power is not for rule, not for battle, and her intellect is not for invention or creation, but for sweet orderings,” (Gubar 816). Here a male demonstrates that a woman should be nothing more than a “domestic goddess”, ruling over only the kitchen and the children, yielding to the command and power of a man.

An angelic life of submissive behavior symbolizes “both heaven and the grave,” (Gubar 817). According to Gilbert and Gubar, this “selfless” lifestyle of ideal Victorian women leads to a life of death. However, there is not really much a woman can do if she wishes to carry on in this type of society. Women have been rebelling against this tradition since Biblical times. Lilith, Adam's first wife, refuses to live this life of submission and is ultimately sentenced to live with the demons. Although this example is harsh, it is not unlike consequences of today. Women still have to accept the fact our patriarchal society believes that men and women are not equal; there are roles that each gender must fulfill in order to maintain the status quo. Lilith's story emphasizes that “a life of feminine submission [….] is a life of silence[...] while a life of female rebellion, of 'significant action' is a life that must be silenced,”(Gubar 824).

As a young women, I do not want to live a life of silence. I would rather fight for this idea of independence and risk being silenced, rather than sentence myself to a life of submission. However, despite my desire to be revolutionary, I will eventually have to fulfill my female role in society. Does this mean we all have to compromise if we all want to have a family and relationships?

Males throughout literature and the arts are always given various options. They can be good, evil, or even both. They can be independent while simultaneously involved in a relationship.

When, if ever on my time on this planet, will women be given those options with multi-dimensional characteristics? Or will a woman's desire for her independence sentence her to forever be the “madwoman in the attic”?

Works Cited

Gilbert, Sandra, and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic. Literary Theory an

Anthology. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2004. 813-25. Print.