“Every angel in the house-'proper, agreeable, and decorous' 'coaxing and cajoling' hapless men-is really, perhaps, a monster, 'diabolically hideous and slimy” (Gilbert and Gubar 820)

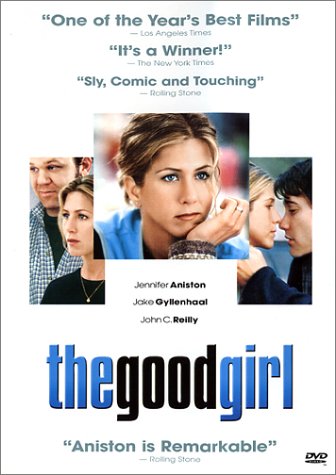

Throughout various types of art (literature, film, music, etc) woman are constantly defined as either “good or “evil”. From fairy tales such as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” to novels such as Jane Eyre, female protagonists are often depicted to be either “pure and gentle” or “malicious and deceitful”. Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar further explore this dichotomy with their work “The Madwoman in the Attic.” These feminists explain that male authors have created female characters that embody either an angel or a monster. Gilbert and Gubar claim that in order to transcend this angel-monster dichotomy, females must destroy these polar opposites so that a "truer" synthesis may emerge for female characters. However Miguel Arteta's film The Good Girl proves that instead of destroying these two opposites, the consequences of the angelic or monster state remain even after the actions were committed in the past, yielding a third type of character that is both angel and monster.

In “The Madwoman in the Attic” Gilbert and Gubar suggest that the first way to transcend this “angel-monster” dichotomy is to recognize these constructions and destroy them. They claim, “Women must kill the aesthetic ideal through which they themselves have been 'killed' into art. […..] All women writers must kill the angel's necessary opposite and double, the 'monster'” (Gilbert and Gubar 812). Women must recognize these judgments male authors have given to them, proving that females do not fall under one classification or another. Instead, Gilbert and Gubar argue, women fall under a third category, an entirely new entity far from these polar opposites. Gilbert and Gubar's article encourages female authors to deconstruct these characters that have been present throughout literature since Biblical times and ultimately find their own feminine character. These radical authors must “revise” the patriarchal society in which most novels are placed, thus eliminating this confining binary.

At the start of the film, Justine appears to be an embodiment of this angel role. Just as male authors have constructed the angelic, loyal wife, Justine appears to have fulfilled her wifely duties. Theorist Emma Dominguez-Rue describes what it means to be eternally feminine: “The cult of True Womanhood conveniently idealized maternity and defined the virtues of obedience, piety, and passivity as essentially feminine" (Dominguez-Rue 425). Gilbert and Gubar claim that although this virginal state in the male perspective suggests that this traditional femininity is deemed heavenly, they believe it suggests a loss of power between the sexes. They explain, “Their 'purity' signifies that they are, of course, self-less, with all the moral and psychological implications the word suggests,” (Gilbert and Gubar 814). By personifying this “eternal feminine” women are, by definition, giving up their individual control. In “The Good Girl', Justine feels powerless in the world she finds herself in. She cannot fully communicate with her husband and her job requires no intellect or emotion; it is as though every day she must get herself through the motions of life. Justine is truly self-less in her everyday existence; her “sleep-walking” life revolves around her oblivious husband and her seemingly happy co-workers.

Justine is finally “awoken” when she meets a fellow co-worker named Holden. He is about twenty-two years old, always alienating himself from the rest of the world. Justine immediately notices his isolated behavior, admiring him for his dismissal of the outside world. Holden does not act happy all the time like everyone else, instead he reads books like The Catcher in the Rye that comment upon the hypocrisy in the world. Their relationship begins when Justine offers Holden a ride home,, where she is introduced to his lifeless parents and his depressing short stories. She finds herself infatuated with Holden's irregular behavior, realizing that they both share a hatred and hopelessness for the world around them. This infatuation sparks a sexual relationship where Holden ignites Justine's youthful passion.

Justine's adultery immediately “kills” off her once-angelic character. She instead focuses her attention on Holden and the supposed “brightness” he brings into her dull existence. Despite her happiness, Justine has transformed into a selfish monster. Gilbert and Gubar explain that this figure is the ultimate threat to patriarchal society. They describe, “ Emblems of filthy materiality, committed only to their private ends, these accidents of nature, deformities, meant to repel “ (Gilbert and Gubar 820). This monster that Justine has become has ultimately isolated her from the rest of the world, leaving Holden as the only person who understands her. These theorists claim that male authors valued the angelic woman because “all characteristics of a male life of 'significant action'-are monstrous in women precisely because [they are] 'unfeminine' and therefore unsuited to a gentle life of 'contemplative purity'' (Gilbert and Gubar 818). Justine has finally taken control of her happiness, choosing to partake in an affair that finally fulfills her needs. She has disregarded the expectations angelic women are supposed to meet; she has found her own sexuality and does not care about pleasing anyone else. Gilbert and Gubar describe this monstrous role assigned by male authors. They say, “Women use their arts of deception to entrap and destroy men, and the secret, shameful ugliness of both is closely associated with their hidden genitals-that is, with their femaleness” (Gilbert and Gubar 820).

Justine's new-found sexuality parallels Jonathon Swift's depiction of monstrous females. The theorists explore this model: “For Swift female sexuality is consistently equated with degeneration, disease, and death” (Gilbert and Gubar 821). In The Good Girl, Justine's adultery yields the same results. Gwen, one of her fellow co-workers, gets food poisoning from a box of blackberries she got from a fruit stand on the road. She gets horribly sick and is rushed to the hospital. Meanwhile, Justine is with Holden, completely disregarding her sick friend. Mirroring Swift's model of the degenerate woman, Gwen dies before Justine gets a chance to say her goodbyes. The adulteress is so consumed by her affair that she fails to recognize the destruction that is occurring in her real life. Her immoral behavior somehow brings forth death and disease in her world. The monster Justine has become has stained her morality; she is stuck in a life that will undoubtedly result in unforgiving consequences.

Justine and Holden's relationship continues on without any trace. However, just like most monsters eventually reach their fatal end, Justine's secret is soon revealed. Bubba, her husband's best friend, spots Justine and Holden leaving the motel. He soon realizes that Phil's wife has been having an affair behind his back. Bubba does not know how to react, debating whether or not he should tell Phil the truth. Torn, Bubba threatens to blackmail Justine into having sex with him in order to prevent him from revealing her secret. Monstrous Justine eventually agrees to this arrangement and sleeps with Bubba. Just as Justine leaves Bubba's bed, she realizes that Holden has been watching them the entire time.

The Justine that allows herself to yield to Bubba's outrageous demands is a far cry from the Justine who is desperate to please everyone. Justine now personifies a full-fledged monster, similar to the characters male authors have previously created. Gilbert and Gubar discuss Spenser's The Faerie Queen in which a female monster is 'most lothsome, filthie, foule, and full of ville disdaine “(Gilbert and Gubar 820). The monster, as constructed by these male authors, leads a life full of deceit and entrapment. Justine now finds herself lying to everyone, losing control of her own reality along the way.

As this affair with Holden continues, Justine and her husband visit the doctor to find out if Phil is able to produce offspring. A few weeks later, the doctor calls and informs Phil that he is infertile. However, just a few days earlier Justine announces she is pregnant. She knows that the baby must be Holden's, but cannot bear the thought of telling her husband the truth. At this point, she is stuck at the crossroads of her life. She can either continue to live her robotic lifestyle with her passionless marriage and depressing job, or she can act on her impulses and run away with Holden, perhaps leading to the life she was supposed to live. In this scene, Justine finds herself at a street intersection, waiting for the light to turn green and lead her to her fate. When the light changes, she drives back to the drugstore, informing her manager about Holden's participation in a store robbery. The police track down Holden at the motel where he had earlier told Justine to meet him after work. Meanwhile, Justine returns home to her husband to celebrate her maternity, convincing Phil that the doctor was wrong and the baby is his.

Justine's decision to return back to Phil and the drugstore is her desire to seemingly correct her mistakes. The consequences of her affair have finally begun to appear in her life. She wants to go back to being that angelic wife she once was. Justine realizes that a life with Holden could not be her life at all; too many people would be hurt and disappointed and terrible consequences would come. She goes back to Phil and begins to put on that “selfless” mask she once bore.

Justine's return to this selfless state may actually represent a fear of the unknown. In “The Madwoman in the Attic,” Gilbert ad Gubar tell the story of Lilith, Adam's first wife in the Bible. She considers herself to be equal to Adam because like him, she was also created by dust. She refuses to lay next to him and prefers “punishment to patriarchal marriage” (Gilbert and Gubar 822). Her punishment is that she is locked into a vengeance of child-killing, killing even her own children. Gilbert and Gubar explain that Lilith's story “represents the price women have been told they must pay for attempting to define themselves” (Gilbert and Gubar 823). Women are afraid of what will become of them if they fail to fulfill this angelic wifely role. Like these women, Justine is fearful for what may become of her.

Even though Justine wants to return back to her loyal life, her angel is now an angel-monster. Phil finds a credit card statement with her motel purchases on it and asks Justine if she has been having an affair. She confesses, never revealing her partner's identity. She reassures Phil that the baby is his, even though she knows in her heart it is Holden's child. Her attempt at correcting all the mistakes in her life is only masking the truth. She appears on the outside to be an angel, but her deception, lies, and secrets prove that her inner identity is still a monster. This “double-ness' that women can create instills fear in male authors. Gilbert and Gubar state, “Because these other woman can create false appearances to hide their vile natures, they are even more dangerous” (Gilbert and Gubar 820). Similar to Spenser's character Errour, Justine remains to possess both angelic and monstrous qualities. She has the desire to correct her life, but her past decisions only perpetuate even more deceit and dishonesty.

The realization of the angel-monster in literature is actually one of both power and expression. In one article reviewing “The Madwoman in the Attic”, the critic explains that this hybrid allows females to express their suppressed ideas. Helen Mogen claims, “Through a kind of 'double talk' at which women writers became peculiarly adept, patriarchal literary conventions could be followed and yet subverted. So each of the writers examined in this book has herself an evil 'double': her own 'madwoman' who creates a subject that represents her only means of legitimate expression and stands as a metaphorical statement of literal experience” (Mogen 227). This opportunity to explore this realization, through both literature and the real world, finally gives women the chance to reveal their true feelings. Many theorists rejoice at that idea that all women have the angel-monster within them. In the article “The Madwoman and her Languages: Why I Don't Do Feminist Literary Theory”, Nina Bayum claims that “women presently existing contain the madwoman within their psyche” ( Bayum 48). This idea allows women to accept the madwoman as part of her own identity, thus allowing them to express thoughts they may otherwise see as inappropriate for their world.

At the end of the film, Justine narrates a story Holden had given to her before he took his own life. Through reading this story, Justine admits that her relationship with Holden was merely a means to escape her own reality. She realizes that it is impossible to escape her real life, eventually accepting the fact that she must continue to live the same way she always has. Justine and her husband celebrate the birth of their new baby girl, who Phil believes is of his own blood. Her daughter is a reminder for Justine's attempt at escaping her own life, a beautiful presence that will forever stir up feelings of deception. Justine has come to the realization that she can either follow the rules and make it through life or she can completely go against her womanly role and face the consequences. Gilbert and Gubar further explain this idea: “A life of feminine submission, of 'contemplative purity' is a life of silence, a life that has no pen and no story, while a life of female rebellion, of 'significant action' is a life that must be silenced, a life whose monstrous pen tells a terrible story” (Gilbert and Gubar 824). They claim that either way a woman must decide, whether it be creativity or in reality, to frame themselves in the angel or monster binary. Gilbert and Gubar suggest that in order for women authors to surpass this dichotomy they must radically revise the patriarchal world in their writings by destroying these two ideas entirely.

Justine's story exemplifies that radically revising structures in the real world is not yet a possibility. As a woman, she must be obedient and selfless. However, this selflessness only promotes selfish motivation that must either be expressed or repressed. Justine is both an angel and a monster; she is a human being that can never be perfect. As Gilbert and Gubar suggest, she “kills” both the angel and the monster only to prove that they are both present in women everywhere. However, unlike the theorists' suggestion that a radical entity will be created, Justine's story suggests that women are in actuality an angel-monster. This combination destroys the traditional dichotomy created by male authors and proves that women are neither all good or all bad; it is just a matter of how much they wish to repress their true desires and thoughts. Gilbert and Gubar suggest that this repression lies the true destruction of a woman's life. They claim, “For to be selfless is not only to be noble, it is to be dead. A life that has no story[....] is really a life of death, a death-in-life. The idea of contemplative purity evokes, finally, both heaven and the grave” (Gilbert and Gubar 817). By suppressing oneself, just as Justine decides to do despite her desire to escape, she has ultimately sentenced herself to her own death. Her choice of silence is the most fitting for the real world. It is not yet possible to completely revise these traditional patriarchal constructions without facing severe consequences. Justine's case suggests that women need to first accept that both of these beings are present within themselves and only then can accept their identity.

Although Justine desires to return to her angelic life, her realization of her inner “angel-monster” or her “madwoman” has liberated her from the conventions placed upon her existence. Many critics see this discovery as a part of the female experience. Marta Caminero-Santagelo suggests that “the 'return' is not an escape from a dangerous condition, but an expanded state that includes the understanding gained by the 'withdrawal and deep introspection' of madness” (Caminero-Santagelo 123). Justine's return to her life does not destroy the feelings she experienced during her “monstrous” days. Instead, her transition from angel to monster to a hybrid of the two ideas allows her to understand her self even more. She must realize that as a women she is this entity, hopefully propelling her to express her ideas without fear or limits of the constructions placed upon her.

Both “The Madwoman in the Attic” and “The Good Girl” illustrate that women will eventually face a cross-roads in their life. Both also suggest that they do not choose to frame themselves as either an angel or a monster. Ideally they must accept their inner madwoman and speak out against the patriarchal world that has repressed their true nature. In reality, women must experience the same “double-ness” that Justine faces . They need to acknowledge themselves as an angel-monster, a character that is ever present in human beings, and only then can they determine their fate. Justine will never be an angel again. However, she chooses to submit herself to her society even though she realizes that this angel-monster will forever be in her. A radical change for women would be Justine's decision to expose this angel-monster to the world, revealing her true identity regardless of the consequences. Gilbert and Gubar wanted female authors to try this in their writings, but perhaps this choice would be revolutionary if it was revealed in the patriarchal society that has suppressed women since the beginning of time.